Learn the judicial foreclosure process, including borrower protections and lender responsibilities.

"Foreclosure" happens when you fall behind on your mortgage payments, and the lender uses state procedures to sell your house to repay the debt. The process works differently in different states. In some states, the lender must go through court to foreclose, called a "judicial foreclosure." In others, the lender can choose to bypass the court system and use a nonjudicial foreclosure process.

A judicial foreclosure requires the lender to file a lawsuit and get a court order before the property can be sold to satisfy the debt. It is often a lengthy and complex procedure that might take several months or even years to complete, depending on the jurisdiction and the specifics of the case. So, this process provides borrowers with more time to contest the foreclosure and potentially work out a loss mitigation option (a foreclosure alternative).

Additionally, states that use a judicial foreclosure process often provide a right of redemption, which allows the borrower to reclaim the property after the sale by paying off the full debt. Foreclosed borrowers sometimes get the right to live in the home (payment-free) during the redemption period.

- How the Judicial Foreclosure Process Works

- What States Use the Judicial Foreclosure Process?

- Homeowner Rights During Judicial Foreclosure

- Judicial Foreclosure Timeline

- Deficiency Judgment After Judicial Foreclosure

- Impact of Judicial Foreclosure on Your Credit Scores

- Can You Stop Judicial Foreclosure?

- Learn More About Foreclosure

- Getting Help With a Judicial Foreclosure

How the Judicial Foreclosure Process Works

Again, in a judicial foreclosure, the lender must file a lawsuit to start the process. A judicial foreclosure typically takes several months or, in some cases, years. A prolonged foreclosure process gives you time to work out a way to avoid foreclosure or look for another place to live and save money for the future.

Another advantage to a judicial foreclosure is that you can raise any legal defenses to the foreclosure in court without filing your own lawsuit.

What States Use the Judicial Foreclosure Process?

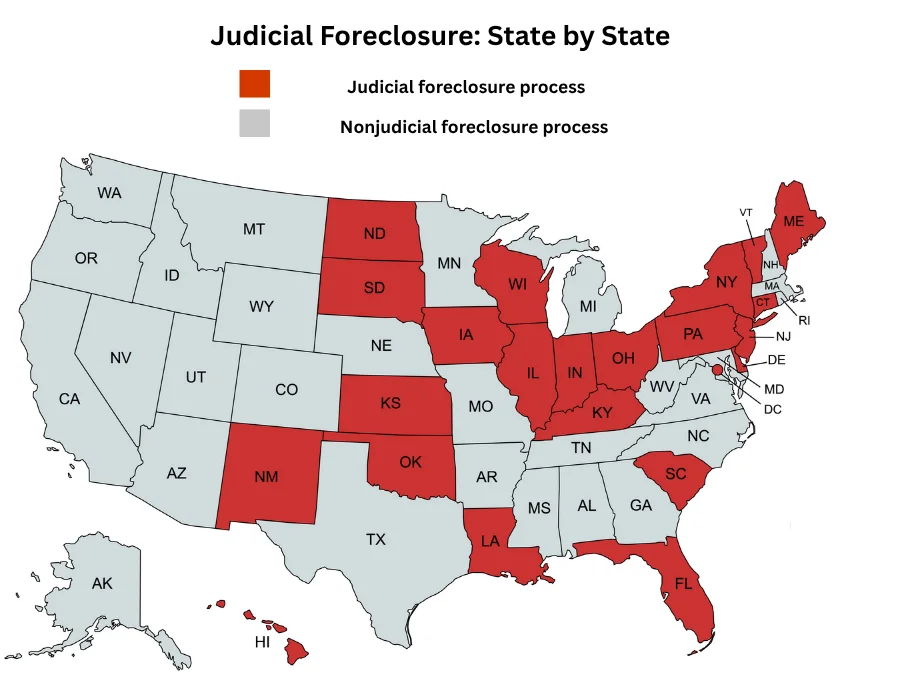

With some exceptions, foreclosures go through court in the following states: Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana (executory proceeding), Maine, New Jersey, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma (nonjudicial foreclosures allowed, homeowner can request judicial foreclosure), Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota (nonjudicial foreclosures allowed, homeowner can request judicial foreclosure), Vermont, and Wisconsin.

Foreclosures are usually judicial in the District of Columbia, Hawaii, and New Mexico. Nonjudicial foreclosures are allowed in those states, but that process is rarely used.

The following graphic shows states where foreclosures usually go through court.

Homeowner Rights During Judicial Foreclosure

Homeowners facing a judicial foreclosure have important legal rights throughout the process. Federal and state laws provide homeowners with these rights, as do the terms of the mortgage or deed of trust. These rights typically include receiving proper notice of the foreclosure, the right to contest the foreclosure if there are valid defenses, the right to be informed about and pursue a loss mitigation option (such as a loan modification or repayment plan), the opportunity to catch up on missed payments (called "reinstatement"), and, in some states, the right to redeem the property even after the foreclosure sale by paying off the full debt.

In addition, borrowers are entitled to remain in the home until the foreclosure sale is completed and, in some cases, through a post-sale redemption period. If the foreclosure sale results in surplus funds after paying off the mortgage and other liens, the former homeowner might be entitled to those excess proceeds.

Judicial Foreclosure Timeline

The typical duration of a judicial foreclosure can vary widely, but it is generally much longer than a nonjudicial foreclosure due to the involvement of the court system. Because judicial foreclosures require the lender to file a lawsuit and various legal pleadings throughout the process, judicial foreclosures are affected by judges' schedules and court backlogs.

Other common causes of delays in judicial foreclosures include foreclosure mediation programs and bankruptcy filings. Additionally, federal and state foreclosure prevention efforts and homeowner protection laws can extend the timeline. Each of these factors can contribute to a lengthy judicial foreclosure process.

Here's how a typical judicial foreclosure might proceed.

1. You Fall Behind in Mortgage Payments

Under federal law, in most cases, the lender must wait until you're more than 120 days delinquent in payments before starting a foreclosure. (12 C.F.R. § 1024.41 (2025).)

2. Lender Sends a Preforeclosure Notice (Breach Letter)

In many cases, the loan contract requires the lender to send a "breach" letter to the borrower. This letter informs you that a foreclosure will begin unless you make up the missed payments, plus costs and interest. The letter may be sent during the 120-day preforeclosure period.

3. Lender Files a Foreclosure Lawsuit

After the servicer (the company that manages your loan account on behalf of the lender) refers the file to an attorney for foreclosure, the attorney will prepare a "complaint" or "petition" for foreclosure and file it with the court, usually in the county where the property is located. The lawsuit will ask the court for a judgment authorizing a foreclosure sale.

4. You Get Notice About the Lawsuit

The sheriff or a process server will serve you with a summons and a copy of the complaint for foreclosure.

5. You Get a Chance to Respond to the Lawsuit

The summons gives you a deadline by which you must respond to the complaint if you choose to contest or argue the lawsuit, usually between 20 and 30 days. Whether you file a response is up to you.

What happens if you don't respond. If you don't respond, the lender will ask the court for a default judgment and (most likely) automatically win the suit. The court then issues a default judgment authorizing the lender to sell your home.

How to respond to a judicial foreclosure lawsuit. If you answer the suit, you'll have the opportunity to tell a judge why you think you have a legal right to keep your house and that foreclosure isn't warranted. You can raise procedural and substantive defenses. Your answer must be in the format that local court rules require. For example, you'll probably have to create a caption at the top of the first page, which includes the names of the people and businesses involved in the suit, the name and address of the court, and the case number. In your answer, you must include responses to each of the claims made by the lender and any defenses you might have. The foreclosure might be halted or significantly delayed if you have strong defenses.

However, if you file an answer but are in default and don't have a legal defense, the lender will still get a judgment, and the court will allow it to proceed with a foreclosure sale. And even if you win, it might be a temporary victory if the lender can fix whatever problem caused it to lose this time.

Should you file an answer to the foreclosure lawsuit? In some cases, filing an answer isn't in your best interests. You might need to file a different kind of pleading to preserve your rights, and filing an answer to the foreclosure might cause you to lose an important right. For example, a court must have "jurisdiction" (authority) to hear a case. If the lender made an error, such as failing to properly serve you the lawsuit, you could dispute the court's jurisdiction by filing a motion to dismiss. If the court agrees and dismisses the foreclosure, the lender must start the process over. But if you file an answer, you "stipulate" (agree) that the court has the right to hear the matter, and the foreclosure goes ahead. Litigation is complex, and most people do better by getting help from a lawyer.

8. Discovery Phase

If your answer raises issues the court must decide, the suit will probably move to the discovery stage. In this phase, you and the lender get to learn about the evidence in the other's possession. You and the lender can ask for information using discovery tools, including:

- written interrogatories (questions about case-related facts that the other side has to answer in writing)

- requests for the production of documents (a demand requiring the other party to give you specific documents)

- depositions (one party testifies under oath in front of a court reporter), and

- property inspections (one side views real estate or property in the other side's possession).

After discovery, or perhaps before, the lender might file a "summary judgment" motion, which asks the court to decide the case without a trial. The lender will make arguments and provide evidence in its motion.

You can fight the motion by responding to it and submitting your arguments and evidence. If the court decides you don't have a defense, the lender will win the motion, get a judgment, and be able to hold a foreclosure sale. If the judge denies the lender's motion, the court will allow the case to proceed to trial.

7. Court Enters a Foreclosure Judgment and Orders a Foreclosure Sale

If the court decides in favor of the lender (either as part of a default judgment or summary judgment or after a trial), it will enter a judgment ordering the sale of your property to satisfy the debt. Once the court grants the lender a judgment of foreclosure, a notice of the sale might be published, depending on state law. The foreclosure sale will take place on the designated time and date, and the property will be sold to the highest bidder.

At the sale, the foreclosing lender can credit bid up to the total amount of the debt, plus foreclosure fees and costs, while any other parties must bid in cash or a cash equivalent, like a cashier's check. In the majority of cases, the lender will be the high bidder at the foreclosure sale and get ownership of the property.

8. Redemption Period After the Foreclosure Sale

A few states give a foreclosed homeowner some time after the foreclosure auction to redeem the property. In these states, a foreclosed homeowner can recover ownership of the home by reimbursing the successful bidder or paying off the entire mortgage debt.

9. You Voluntarily Leave or Get Evicted

If you don't leave the property when your legal right to remain in the home ends, you'll receive an official notice to leave the property. Exactly when you need to move out depends on state law. You might need to move out after the sale, after the redemption period expires, or after some other event happens, like confirmation of the sale.

Deficiency Judgment After Judicial Foreclosure

If the foreclosure sale price isn't enough to satisfy the mortgage debt (and state law allows it), the lender can ask the court to grant a deficiency judgment. If the lender gets a deficiency judgment against you, you remain responsible for the outstanding balance left on the loan after the foreclosure sale.

However, some states don't allow deficiency judgments under certain circumstances.

Impact of Judicial Foreclosure on Your Credit Scores

A judicial foreclosure will have a negative effect on your credit scores and remain on your credit reports for seven years. Missed payments, along with the foreclosure itself, will damage your credit.

The impact on your credit will be most severe in the first few years, making it harder to obtain new credit. However, this effect gradually lessens over time, especially if you take steps to rebuild your credit, such as paying all of your bills by the due date. It will be completely removed from your credit reports after seven years.

Can You Stop Judicial Foreclosure?

You can stop a judicial foreclosure by working out a loss mitigation option, such as a loan modification, repayment plan, or forbearance agreement, with your loan servicer. These solutions might make the mortgage more affordable and halt the foreclosure process. Filing for Chapter 7 or Chapter 13 bankruptcy can also provide temporary relief through the automatic stay. Chapter 13 offers a structured repayment plan that might allow you to keep your property.

State law or the mortgage terms might allow you to stop a foreclosure by reinstating the loan (paying off past-due amounts) or by redeeming the property before the foreclosure sale (paying off the total mortgage debt).

If you think the foreclosure is improper or that the lender failed to follow required procedures, you may challenge the process in court. Responding to a foreclosure lawsuit can delay or stop the proceedings while the matter is resolved.

In rare cases, government-imposed foreclosure moratoriums may temporarily suspend all foreclosure activity.

Learn More About Foreclosure

To learn more about foreclosure and your options, visit the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development's Avoiding Foreclosure website.

Getting Help With a Judicial Foreclosure

Because foreclosure laws differ by state and every situation is unique, it's a good idea to consult with a foreclosure attorney. A qualified attorney can help evaluate your available options and ensure your rights are fully protected. If you need legal advice, but can't afford a lawyer, you might qualify for free or low-cost legal aid.

Contacting a (free) HUD-approved housing counselor is also a good idea. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau offers information on how to find affordable mortgage help.

- How the Judicial Foreclosure Process Works

- What States Use the Judicial Foreclosure Process?

- Homeowner Rights During Judicial Foreclosure

- Judicial Foreclosure Timeline

- Deficiency Judgment After Judicial Foreclosure

- Impact of Judicial Foreclosure on Your Credit Scores

- Can You Stop Judicial Foreclosure?

- Learn More About Foreclosure

- Getting Help With a Judicial Foreclosure