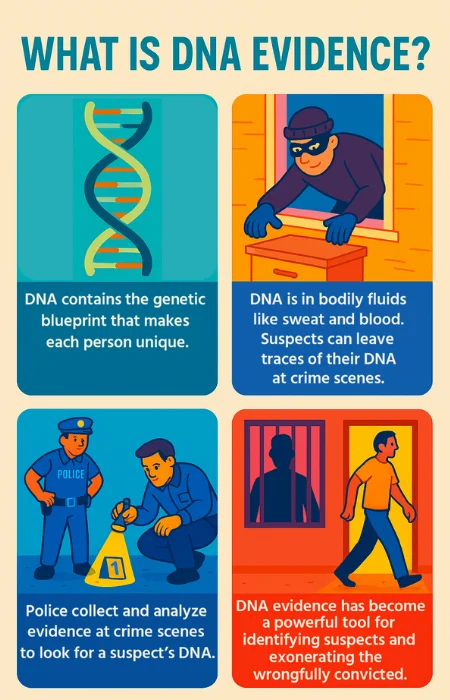

DNA testing can help identify criminal suspects and exonerate the wrongly accused.

DNA evidence has become a powerful tool in criminal investigations and trials. When someone commits a crime, they often leave genetic evidence behind—their unique DNA is present in their blood, in their hair, or even on the objects they've touched. Police can collect these samples and use them to identify suspects.

This article explains how DNA evidence works in criminal cases. We'll discuss what DNA is, how law enforcement agencies collect and test it, and why it's come to be viewed as such a reliable form of evidence. We'll also discuss the history of DNA evidence and its role in exonerating the wrongfully convicted.

DNA and DNA Evidence: Understanding the Basics

DNA is a molecule that acts as a set of instructions for the development and function of every human (and of other living organisms). The chemical compounds in each person's DNA are arranged in an order (called a "sequence") that is are unique to that individual. (The only exception is identical twins, who share nearly identical DNA.) These unique DNA sequences mean that no two people on Earth can be exactly the same.

DNA Evidence Is Physical Evidence

In a criminal trial, evidence is presented to a judge or jury to prove (or disprove) key facts in the case. Evidence can include everything from eyewitness testimony to the opinions of expert witnesses.

DNA evidence is a form of physical evidence—that is, a tangible object that supports (or undermines) a link between a suspect and a crime. For example, imagine that someone has their name sewn into a piece of clothing, and that clothing is found at a crime scene. This is physical evidence of a connection between that individual and the crime.

DNA evidence works the same way. People leave genetic traces—including DNA—on the clothes they wear and the objects they touch. There is also DNA in human blood and other bodily fluids. This means police can analyze crime scenes and collect material that might contain a suspect's DNA. If DNA collected at a crime scene matches the DNA of a suspect, it is physical evidence connecting the suspect to the crime.

DNA Evidence Is Circumstantial Evidence

It is important to understand that "physical evidence" is different from proof that someone committed a crime. For example, finding someone's clothing at a crime scene does not automatically mean they committed the crime, or were even there when the crime occurred. The same is true of DNA evidence.

In both cases, the clothing and the DNA are circumstantial evidence supporting an inference that a specific person was at the crime scene. You still need other evidence to prove that a crime occurred and that the suspect committed it. Circumstantial evidence is different from direct evidence, like eyewitness testimony. If you believe that direct evidence is reliable, it proves a fact by itself—you don't need any additional information.

One type of evidence isn't "better" than the other. For example, circumstantial DNA evidence can reveal that direct evidence provided by an eyewitness was mistaken. We'll talk more below about potential issues with the reliability of DNA evidence.

How Is DNA Evidence Collected?

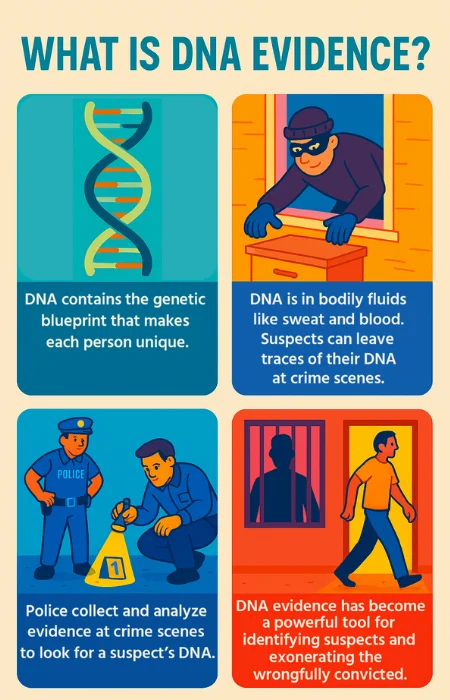

To use DNA evidence in criminal cases, law enforcement:

- collects DNA samples from crime scenes

- obtains DNA samples from suspects, and

- matches crime scene DNA to a suspect's DNA.

Investigators must follow guidelines to ensure that DNA evidence is collected, analyzed, and used properly.

How Do the Police Collect DNA at Crime Scenes?

Law enforcement agencies don't have the time, money, or staff to collect DNA from every crime scene. So, DNA testing is usually reserved for very serious crimes, and for crimes where DNA collection is most likely to help solve the case. For example, DNA is often collected when investigating:

- murder cases

- sexual assault cases, and

- other violent crimes.

When collecting DNA, investigators need to wear protective clothing like masks and gloves, so they don't contaminate DNA at the crime scene with their own DNA. The goal is to collect anything that might contain samples of the perpetrator's DNA. This can include:

- Blood and other bodily fluids. Sometimes these fluids are collected directly from the crime scene with swabs. Other times, entire items (like bloody clothing) might be removed from the scene for testing.

- Hair. It's easiest to collect a useful DNA sample from the hair follicle, but it's sometimes possible to collect it from the hair shaft itself.

- Items the perpetrator may have touched. A person can leave their DNA on an object just by touching it. But items like drinking cups and cigarette butts are better options for collecting a useful DNA sample.

Two important rules for collecting and testing DNA must be respected throughout the process, starting at the crime scene:

- The chain of custody must be maintained. In other words, there must be documentation of everyone who handles the DNA sample, and everywhere it is stored, from the moment it's collected through when it's used as evidence against a defendant. The same rule applies to all physical evidence—the chain of custody allows judges and juries to make sure that an item presented as evidence is the same item recovered from the crime scene.

- The samples must be handled carefully and stored securely so that the evidence is preserved. This requirement also helps with the chain of custody. For example, DNA samples should be stored in containers that cannot be opened without breaking a seal. This makes it easier to detect both accidental contamination of a sample and deliberate attempts to tamper with evidence.

How Do the Police Get DNA From Potential Suspects?

If investigators recover DNA from a crime scene, they will try to match it to the DNA of a suspect. The police have several options for obtaining the DNA of potential suspects, but not every option is possible or permissible in every case.

After an arrest. In some states, the police are allowed to take DNA samples after an arrest. The samples are taken using a cheek swab that collects cells from inside the person's mouth. The rules for this vary by state. For example, California police collect a DNA sample from any adult arrested for a felony. On the other hand, police in New York state are barred by state law from collecting a person's DNA just because that person has been arrested. But a sample is collected from anyone who's convicted of a felony or misdemeanor in New York.

Search warrants. Sometimes the police can get a search warrant and compel a person to provide a DNA sample, even if the person hasn't been arrested. This kind of DNA collection is a search and seizure under the Fourth Amendment, which means the police need a search warrant. A warrant will be issued if a judge decides that there's probable cause to believe that:

- a crime has been committed, and

- obtaining the person's DNA will provide evidence to help solve the crime.

Voluntary DNA samples. People will often voluntarily provide DNA samples to the police to aid in an investigation. For example, imagine that someone is kidnapped, struggles with their attacker, and escapes. If they provide a DNA sample, it might match DNA collected from a suspect's clothing, body, or vehicle. This would help prove that the crime occurred and that the suspect committed it.

Sometimes the police request so-called "elimination samples" from people with an innocent reason for being at a crime scene or in contact with a victim. This allows investigators to ignore the DNA of these people and zero in on the DNA of potential suspects.

The CODIS database. The Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) is maintained by the FBI. CODIS allows investigators to check DNA collected at a crime scene against:

- DNA collected at other crime scenes

- DNA collected from people who've been arrested for or convicted of crimes, and

- DNA samples from missing persons.

CODIS makes it much easier for investigators to connect DNA found at a crime scene to the DNA of a specific person whose name and sample are in the system. It also allows law enforcement to learn that multiple crimes have been committed by the same person, even if that person's identity isn't yet known.

Genealogy websites. In 2018, police were able to identify and arrest the Golden State Killer because a relative's DNA on a genealogy website provided a crucial lead. California police didn't need the relative's permission to use his DNA, they just needed permission from the website. That's because you lose your Fourth Amendment right to keep your DNA private if you voluntarily share it with a third party. A company's willingness and ability to share customer DNA with police depends on its terms of service, and authorities may be able to get the data with a warrant.

Relatives of a suspect. Sometimes the police will identify a suspect, and then ask one of the suspect's relatives for a voluntary DNA sample. The police are not required to tell the relative why they're asking for the sample. Once they have the relative's sample, they can use it similar to how the police used DNA in the Golden State Killer case.

How Does DNA Matching Work?

Methods for analyzing DNA samples have become more and more sophisticated over the years. Law enforcement agencies now use a process called short tandem repeat (STR) analysis to look for DNA that matches samples recovered from a crime scene.

STR analysis works because the differences that make each person's DNA unique are not spread out equally. Instead, they are concentrated in specific sections of DNA. Scientists can identify and compare these unique sections in two DNA samples. If the sections are different, then the DNA came from two different people. If the sections are the same, then the samples came from the same person.

The accuracy of DNA matching depends on how much DNA is recovered from a crime scene. If there is very little DNA, or it has degraded, there may not be enough unique sections to perform the best analysis. But, when comparing two good DNA samples, scientists estimate that the odds of a mistaken match are one billion to one.

When Was DNA Evidence First Used?

Law enforcement agencies and prosecutors have been using DNA evidence since the mid 1980s.

In 1986 and 1987, British police became the first to use DNA evidence to investigate and solve a crime. They were able to use DNA samples to confirm that two murders had been committed by the same perpetrator—and to exonerate a young man who had falsely confessed to one of the killings.

The police continued their investigation, and requested DNA samples from men who lived near the crime scenes. The murderer, Colin Pitchfork, attempted to evade suspicion by paying another man to impersonate him and provide a DNA sample. When the police found out, they arrested Pitchfork and he confessed to the crimes.

Tommie Lee Andrews was the first person convicted in the United States because of DNA evidence. Andrews had burglarized a home and sexually assaulted the woman who lived there. Andrews was arrested soon after the crime, but Florida police and prosecutors were concerned they did not have enough evidence against him. They turned to DNA testing, which identified Andrews as the perpetrator in their case and in a previously unsolved sexual assault.

How Reliable Is DNA Evidence?

DNA evidence is now widely accepted as extremely reliable. However, that reliability depends on the proper handling and testing of DNA samples. In addition, prosecutors and witnesses for the prosecution may make inaccurate claims about what certain DNA evidence actually proves.

DNA Samples Must Be Handled Properly

One of the most famous cases involving DNA evidence did not end with a conviction. O.J. Simpson was arrested in 1994 for the murder of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman. At the time, the use of DNA evidence was not yet routine. Simpson's attorneys challenged the DNA evidence by arguing that the samples had been collected and stored sloppily.

Simpson's high-profile trial and acquittal increased public understanding of the value of DNA evidence. It also led law enforcement agencies to adopt better procedures for collecting and analyzing DNA samples. If these procedures are not followed, a defendant can cast doubt on the validity of the evidence.

The Limitations of DNA Evidence Must Be Understood

Even if DNA samples are collected and tested properly, scientists or prosecutors could overstate the reliability or usefulness of the evidence. It's important to recognize the potential limitations of DNA evidence.

Not all DNA matching is equally accurate. Even if DNA is present at a crime scene, there may not be enough of it to get the most accurate match with a suspect's DNA.

A person's DNA could be at a crime scene even though they weren't. As collection and testing gets more sophisticated, it becomes easier to detect very small amounts of DNA. This increases the chance that, for example, someone's DNA could end up at a crime scene because they touched an object that was later brought to the scene by another person.

DNA statistics can be presented inaccurately. We mentioned above that, with good samples and accurate testing, the chances of a mistaken DNA match are one billion to one. But this doesn't mean there's only a one-in-a-billion chance that the identified person is innocent. Other evidence must still be used to prove the defendant's guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

Using DNA to Exonerate the Wrongfully Convicted

DNA evidence has proven to be a powerful tool in proving the innocence of prisoners who were tried before DNA testing in its current form was an option.

If bodily samples, such as blood or semen, were collected from the crime scene or victim, and that evidence is still available for DNA testing, it can be compared to the DNA of the person convicted of the crime. If the prisoner's DNA doesn't match the crime-scene DNA, that can be a powerful reason to conclude that the prisoner is innocent and should be released.

DNA evidence has thus far resulted in the release of about 250 wrongfully convicted prisoners (many of whom had served many years in prison or were even facing the death penalty). Most instances of erroneous convictions are due to mistaken eyewitness identifications.

Perhaps the most well-known organization that pursues these types of cases is The Innocence Project, which was founded by the two attorneys who attacked the DNA evidence in the O.J. Simpson case.

Learn More About DNA and Forensic Evidence

DNA matching has changed how crimes are solved and made it easier both to identify the guilty and exonerate the innocent. But, as we've seen, DNA samples must be carefully collected, stored, and analyzed to be strong evidence in a criminal case. If you're involved in a criminal case, an experienced criminal defense attorney should be able to help you understand how the information in this article could applies to your situation.