Learn how defendants can challenge fingerprint evidence used in criminal investigations and trials.

Fingerprint evidence has been used in American criminal trials for more than a century. Although not as sophisticated as other high-tech crime-solving methods, like DNA analysis, fingerprint analysis remains a primary identification method used in criminal investigations and cases. One reason for its longevity and popularity is that it's particularly accessible to juries: A juror doesn't need a Ph.D. or a scientific lecture on genetics to understand that each person's fingers contain a unique contour map of ridges and whorls. However, despite its longstanding use and acceptance by judges, the lack of scientific evidence backing up fingerprint analysis has increased scrutiny on just how reliable this evidence is.

- What Is Fingerprint Evidence?

- Types of Fingerprint Evidence

- How Fingerprint Examiners Compare and Match Fingerprints

- Use of Fingerprint Evidence in Criminal Cases

- How Reliable and Accurate Is Fingerprint Evidence?

- Defense Strategies to Challenge Fingerprint Evidence

- Examples of Fingerprint Evidence Used in Criminal Cases

- Working With a Lawyer

What Is Fingerprint Evidence?

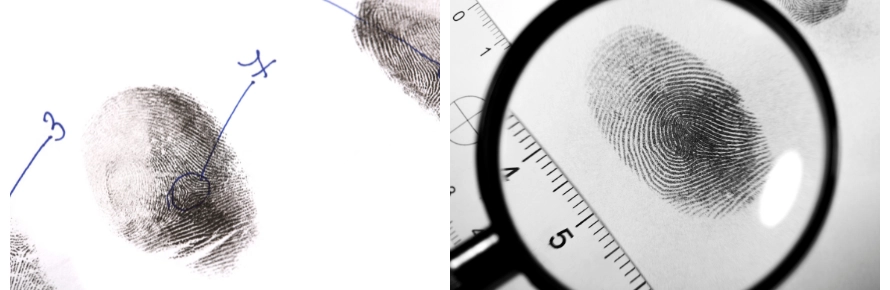

Fingerprint evidence is one type of forensic evidence used to identify individuals. Fingerprints contain friction ridges that leave residue impressions on surfaces. An examination of these friction ridges—whorls, arches, and loops—can be used when comparing different prints to see if they're a match. Identification using fingerprints is based on the (unproven) assumption that no two persons share the same fingerprints.

Types of Fingerprint Evidence

Most fingerprint evidence falls under one of two categories—latent prints or known prints.

Latent Prints

Latent prints are invisible residue prints commonly found at a crime scene. To lift the prints, technicians use various chemical, physical, or lighting techniques to develop visible prints so they can be photographed or digitally enhanced.

Latent prints are often partial impressions with inconsistent quality depending on what the person touched and how. For instance, fingerprint quality varies depending on the type of surface touched (smooth, bumpy, solid, or porous), the length and type of contact, the amount of pressure used, and the presence of external factors (like humidity, dirt, or excessive perspiration).

Known Prints

Known prints (also called "tenprints") are fingerprints taken from a known individual, typically during the booking process or for a background check. These prints are generally kept in government databases. Officials take known prints in controlled settings, making them fairly reliable and of good quality. Ink-and-paper prints are still sometimes used, but most often, officials use digital scans to carefully capture a clear and complete image of each finger and both thumbs.

Comparing Known Prints to Latent Prints

Known prints serve as a reference for comparison to latent prints. Comparing fingerprints might lead to an identification, rule out a suspect, support other evidence, or winnow down a suspect list.

How Fingerprint Examiners Compare and Match Fingerprints

Fingerprint examiners use a method called ACE-V to examine, compare, and match latent fingerprints to known prints. ACE-V stands for analysis, comparison, evaluation, and verification.

Humans vs. Machines

Unlike what we see on TV (where high-tech computers do all the work), fingerprint analysis is primarily a manual process that uses visual and subjective comparisons by two human examiners.

Computer technology comes into play when police don't have a suspect's fingerprints. In this case, the experts will feed the latent prints into a government database with millions of known prints. Computer algorithms compare features of the latent prints to the known prints and generate potential matches. These potential matches go to fingerprint examiners for manual evaluation.

ACE-V Methodology

Fingerprint analysis using the ACE-V methodology involves the following steps:

- Analysis: The examiner assesses the print to determine its quality for comparison. Part of this analysis examines the various levels of detail on the print, including ridge flow (arches, loops, and whorls) and their unique characteristics (location, direction, patterns, and attributes).

- Comparison: An examiner compares the latent print to known prints by reviewing their ridge flows and characteristics.

- Evaluation: The examiner determines whether the prints have sufficient similarities to be considered a match, a non-match, or inconclusive.

- Verification: A second examiner will review the first examiner's conclusions and either verify or refute their findings.

Depending on agency protocols, the second examiner does not always replicate the entire ACE process. Sometimes, they limit their review to the ultimate findings. (Critics of this review process note the potential for confirmation bias and advocate for blind verification, meaning the second examiner doesn't know the results from the first examiner.)

Use of Fingerprint Evidence in Criminal Cases

Prosecutors commonly introduce fingerprint evidence as a way to place a defendant at the scene of the crime, tie them to a weapon or other object, or show they came in contact with a victim.

Fingerprint evidence has been admissible in American criminal cases for over a century. Even with newer technologies available (like DNA and other biometrics), fingerprint comparisons routinely make it into criminal cases and courtrooms. But judges and even the fingerprint experts are taking a much more measured approach to the reliability of such evidence than they did a few decades ago.

It had been common for fingerprint experts to make claims of 100% accuracy in a match. But many scientists and scholars have since challenged the scientific validity of fingerprint analysis, and judges have taken notice.

How Reliable and Accurate Is Fingerprint Evidence?

Unlike DNA analysis and some other forensic techniques, fingerprint evidence lacks scientific studies and peer reviews to support its methodology, reliability, and accuracy. Even the basic foundation of fingerprint identification rests on the untested assumption that no two sets of fingerprints are alike.

No Meaningful Studies

A 2016 government report found it "distressing" that meaningful studies on the accuracy of fingerprint examinations were lacking and that, for the most part, "validity [in this field] was assumed rather than proven." This group of scientists and engineers found only two appropriately designed studies on the accuracy of fingerprint analysis. Based on these studies, they concluded that false positive rates were much higher than the general public would believe based on longstanding claims of accuracy. One study found that errors in latent fingerprint analysis yielded a false positive rate of 1 in 18 conclusive examinations. At most, they could only conclude that fingerprint examiners produce correct answers "under some circumstances...at some level of accuracy." (Forensic Science in Criminal Courts (Sept. 2016).)

Challenging the Validity and Accuracy of Fingerprint Analysis

Defense attorneys have tried to get judges to exclude fingerprint evidence based on a lack of scientific reliability. However, this has proven difficult and rarely successful. For the most part, judges allow the evidence and let the jurors weigh its probative value and credibility. (U.S. v. Crisp, 324 F.3d 261 (4th Cir. 2003); U.S. v. Llera Plaza, 188 F.Supp.2d 549 (E.D. Pa. 2002).) With this being the case, defense attorneys generally use cross-examination to educate jurors on the limitations and shortcomings of fingerprint analysis and reliability.

Before the expert begins testimony, the defense might ask the judge to limit or prohibit certain testimony from the examiner. For instance, the attorney might ask the judge to prohibit the examiner from testifying that fingerprint analysis is 100% accurate or can identify a match with absolute certainty. The defense can also ask the judge to give a cautionary instruction to the jury explaining the probative value of fingerprint evidence and their duty to consider the credibility and validity of such evidence.

Defense Strategies to Challenge Fingerprint Evidence

Defense attorneys can also challenge fingerprint evidence and analysis in the following ways.

No Connection to the Crime

Connecting the fingerprint to the crime is essential to the prosecution's case. Finding a fingerprint (allegedly) matching the defendant only means that the defendant was at the location or touched the item at some time—not necessarily at the time of the crime. Suppose the defendant lived with the victim or worked near the crime scene. It's plausible the defendant could have left those prints many different times in daily life. These possibilities may place reasonable doubt in the minds of the jurors.

Broken Link in the Chain of Custody

Judges won't allow evidence to come into a case if the party seeking to introduce it can't establish a reliable chain of custody. For fingerprint evidence, this means the prosecution must show that the print came from the crime scene or object, was properly lifted, and hasn't been tampered with since. Usually, the agent or technician who processed the crime scene will need to explain their procedures for lifting the prints and getting those prints to the lab. If the defense can identify gaps in the chain of custody or actions that might have compromised the evidence, the judge might not let the prosecution introduce the evidence.

Faulty Findings and Methodology

If the evidence makes it into court, the defense attorney can vigorously cross-examine the fingerprint examiner's methodology and findings. For instance, the attorney might question the quality of the latent image, the accuracy and type of technique used to lift the print, what methods were used to compare the prints, and whether and how the comparison was validated.

They can also question the ACE-V process. While it sounds scientific (enough), no universal or scientifically researched standards exist for evaluating fingerprint features and characteristics. The analysis, comparison, and evaluation stages rely on an examiner's subjective judgment, rather than objective criteria.

Not Qualified as an Expert

The attorney can also question the examiner's educational background and qualifications to be an expert. Currently, no standard training or formal education requirements exist to be a fingerprint examiner. Not all court experts need a specific degree or formalized training, but they do need to be competent in their field. When evaluating an examiner's qualifications, judges may review their educational degrees, training and experience, certifications, and familiarity with the particular techniques involved—just like they do with other experts. The fingerprint examiner cannot testify as an expert until the court allows it. (Fed. R. Evid. 702 (2025).)

Examples of Fingerprint Evidence Used in Criminal Cases

Fingerprint evidence can be useful in criminal investigations when examined following proper protocols and supported with corroborating evidence. Below is an example of where the FBI succeeded in these areas and one where it didn't (which ultimately became an international blunder).

30-Year-Old Cold Case Solved

In 1978, an unknown person stabbed and killed Carroll Bonnet in his Omaha apartment. The killer left fingerprints and palmprints in the bathroom and stole Bonnet's car, which was later found in Illinois. Investigators processed prints found in the apartment and car but couldn't identify a suspect, and the case went cold.

Thirty years later, a technician fed the original prints through the FBI database and identified Jerry Watson as a match. Watson was serving prison time in Illinois. A detective reopened the case and found corroborating evidence linking Watson to the crime. Prison officials were set to release Watson in only a few days. Instead, officials charged him with murder, and Watson was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

Misidentification of Madrid Train Bombing Suspect

In 2004, the FBI messed up big time when it incorrectly tied a fingerprint associated with a train bombing in Madrid, Spain, to an Oregon attorney. Spanish authorities had found latent fingerprints at the crime scene and sent them to the FBI. Three FBI examiners matched the prints to Brandon Mayfield. Despite doubts from Spanish authorities regarding the FBI's conclusion, the FBI arrested and detained Mayfield. Further investigation revealed the match was incorrect. The FBI initially blamed its error on substandard quality prints. But an internal investigation found that, among other errors, FBI examiners failed to correctly apply the ACE-V method.

Working With a Lawyer

It's always a good idea to have a criminal defense attorney or public defender represent you in a criminal case. When forensic evidence is involved, it can also be helpful to hire your own expert to refute the government's findings.

- What Is Fingerprint Evidence?

- Types of Fingerprint Evidence

- How Fingerprint Examiners Compare and Match Fingerprints

- Use of Fingerprint Evidence in Criminal Cases

- How Reliable and Accurate Is Fingerprint Evidence?

- Defense Strategies to Challenge Fingerprint Evidence

- Examples of Fingerprint Evidence Used in Criminal Cases

- Working With a Lawyer