The crime of murder explained and its relation to homicides, along with examples, penalties, and defenses.

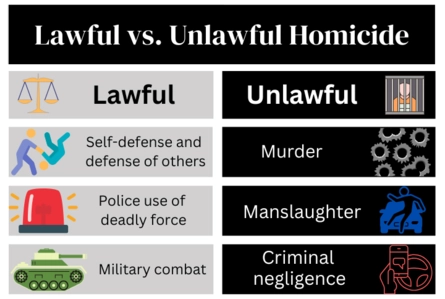

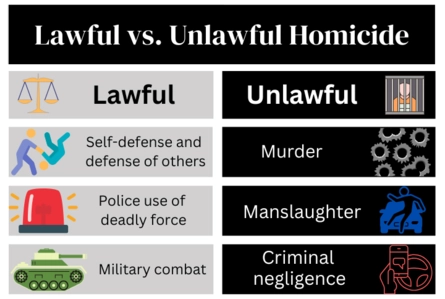

Homicide is a legal term for any killing of a human being by another human being. Homicide itself is not necessarily a crime—for instance, a justifiable killing of a suspect by the police and a killing in self-defense are legal homicides. Murder is an example of an unlawful homicide.

Below we review the legal definitions of murder and homicide, the different degrees of murder and their penalties, and common defenses to murder charges.

What Is Homicide?

The term "homicide" covers lawful and unlawful killings. Homicide is only a crime when committed without a legal justification or excuse.

Lawful Homicides

Some common examples of lawful homicides include:

- military combat killings

- accidental killings (such as a hunting accident)

- killings done in self-defense or defense of another, and

- police officer use of deadly force.

The intentional killings listed above (self-defense, military, and officer use of force) are only justified if certain legal requirements are met. A homicide is accidental if it involves no recklessness or negligence.

Criminal Homicides

Criminal homicides, on the other hand, don't involve a legal justification or excuse. They are punishable under law as murder, manslaughter, or criminal negligent homicide. Punishment for criminal homicide depends on how culpable society deems that person's actions. Homicides that fall under the definition of murder are the most culpable and are discussed here.

What Is the Legal Definition of Murder?

Under common law and statutes, murder is an unlawful homicide committed with "malice aforethought."

Malice aforethought doesn't mean that a killer has to have acted out of spite or hate. It exists if a defendant intends to kill someone without legal justification or excuse. In addition, in most states, malice aforethought isn't limited to intentional killings. It can also exist if the killer:

- intended to cause great or serious bodily harm

- committed an act knowing it would likely cause death or great bodily harm

- committed an act so dangerous it shows extreme and reckless disregard for human life, or

- intended to commit a felony.

Today, statutes, rather than common law, define murder. Murder can involve an affirmative act (like poisoning or shooting someone) or omission (like starvation) to bring about another's death. Motive is not an element of murder.

What Are the Different Degrees of Murder?

Even within the universe of those who kill with malice aforethought, the law regards some as more dangerous and morally blameworthy than others. Many states and the federal government divide murder offenses into at least two degrees, with capital murder or first-degree murder being the most heinous and deserving of the strictest punishment.

Some states list specific actions that constitute first-degree murder and all other murders are second-degree murder. Others identify acts that fall under both first- and second-degree murder. A few states don't use degrees and instead refer to aggravated or capital murder and murder. Lastly, a small number of states don't divide murder into any degrees. In these states, specific acts determine the severity of the punishment.

Below we review how states generally break down the different degrees of murder and provide examples.

What Is First-Degree Murder?

The laws vary somewhat from state to state as to what circumstances make an intentional killing first-degree murder (sometimes called aggravated or capital murder), but the following circumstances commonly do so:

- premeditated and deliberate killings

- killings committed in the perpetration or attempt to perpetrate a dangerous felony (such as arson, rape, robbery, burglary, kidnapping), and

- killings committed by using a bomb, explosive, armor-piercing bullet, or weapon of mass destruction.

Premeditated and deliberate killings. In a premeditated murder, the killer has formed the intent to kill and has had time, however brief, to reflect on the matter. Some states list types of premeditated killings, such as those committed by means of torture, starvation, poison, or lying in wait. An obvious example of premeditation is a wife going to the store, buying a lethal dose of rat poison, and putting it in her husband's tea. But it could also be grabbing a nearby rope to strangle someone if the person contemplated their action.

While committing a dangerous felony. If a defendant intentionally commits a felony and a victim dies as a result, the crime becomes murder—often called "felony murder." Many state statutes list dangerous felonies that can lead to a first-degree felony murder charge—the main five offenses being arson, rape, robbery, burglary, and kidnapping. Other common dangerous felonies include escape from custody, drug sales, and drive-by shootings. An example of first-degree felony murder would be committing arson and a firefighter dies trying to put out the fire or find someone inside.

Use of an explosive, armor-piercing bullet. Several states' definition of first-degree murder includes a killing committed using explosives, bombs, weapons of mass destruction, or armor- or metal-penetrating bullets.

What Is Second-Degree Murder?

In some states and under federal law, second-degree murder is a catch-all. It's everything that's not first-degree murder. Other states identify specific acts that constitute second-degree murder, such as:

- intentional killing without premeditation

- intent to commit great or serious bodily harm resulting in the victim's death

- intent to commit a felony (not listed for first-degree murder) resulting in a victim's death, or

- depraved-mind killings.

Intentional killing without premeditation. Here, the killer acted rashly and impulsively rather than with deliberate and premeditated intent. For example, two family members have a heated argument over money and insurance proceeds. After several hours of verbal and physical altercations between the two, the father leaves the son's room, retrieves a pistol, and goes back to the son's room and shoots him. The father acted intentionally but also irrationally and impulsively in the situation (rather than with premeditation).

Intent to cause serious harm resulting in death. A defendant who intends to cause another serious or great bodily harm can often be charged with second-degree murder if that victim dies. For instance, two bar patrons get into a heated discussion and decide to take it outside. The defendant knocks the other patron down and repeatedly kicks them in the head. The bar patron dies from hemorrhaging in the brain. Even though the defendant only intended to cause great bodily harm and not death, he can still be charged with second-degree murder.

While committing a felony. Some states place felony murder under second-degree murder if the intended felony isn't one of the dangerous felonies identified for first-degree murder charges. One example could be a defendant who engages in a high-speed police chase that results in a pedestrian's or motorist's death. Evading or fleeing police is often a felony offense, and a death resulting from a high-speed change is reasonably foreseeable.

Depraved mind. Usually, murder involves intended harm against a specific person (whether that's intent to kill, injure, or commit a felony). But, some acts are so imminently dangerous to others that society feels the person's extreme indifference to the value of human life is deserving of punishment for murder. For example, someone who drives a vehicle into a crowd or discharges a gun in a subway car and kills someone could be charged with depraved-mind murder. (A few states consider this to be third-degree murder.)

What Is Felony Murder?

As discussed above, most states include felony murder in their first- or second-degree murder statutes. The concept of felony murder tends to be controversial because proof of a defendant's "malice aforethought" isn't required—the law implies it. Basically, the accused's intent to commit the felony gets transferred to the resulting homicide.

Justifying the concept of felony murder isn't too difficult, as in the end, a person is dead due to another's unlawful act. But the resulting punishment for murder is often criticized as excessive and disproportional for an unintended and unanticipated killing. In some states, an accomplice to a crime can be guilty of felony murder even without killing anyone or committing the underlying felony (such as the lookout in a robbery gone wrong).

State laws vary considerably when it comes to what proof is required to sustain a conviction for felony murder. In some states, the death must be a foreseeable result of the initial felony. Many states list "dangerous felonies" that qualify for felony murder charges.

What Are Legal Defenses to Murder Charges?

The stakes are high in a murder case. A robust defense means evaluating all possible defenses and arguments to avoid conviction, reduce the changes, or mitigate the punishment. The prosecution always bears the burden of proving the case beyond a reasonable doubt, which means poking holes in the case and casting doubt are options as well. The exact defense will depend on the facts of the case. Some of the most common defenses and defense strategies for murder charges include the following.

Self-Defense and Defense of Others

A defendant may argue that they killed someone in self-defense or defense of another person. This defense, when successful, typically results in an acquittal. Each state's laws differ as to when the use of deadly force in self-defense or defense of others is justified. Typically, the defendant cannot have been the original aggressor and must have acted reasonably and proportionally to the threat involved. The law may require a duty to retreat.

Alibi or Mistaken Identity

The defense might also argue that the cops got the wrong person or that an eyewitness identification was mistaken. If a defendant can present a solid alibi or effectively discredit an eyewitness, the prosecution's case may fall apart and lead to an acquittal.

Lack of Intent or Premeditation

Another defense strategy is to seek a reduction in the charges to manslaughter or a lesser degree of murder. A defense attorney might argue that the prosecution failed to show the killing was premeditated or intentional. If a defendant acted in a sudden heat of passion or irrationally, charges could be reduced to manslaughter or second-degree murder. Voluntary intoxication could also establish the inability to form premeditation.

Insanity Defense

While there's much discussion regarding the insanity defense, it's rarely used and highly controversial. Even if successful, the outcome isn't acquittal. It's typically lengthy confinement in an institution.

What Is the Punishment for Murder?

Murder carries the harshest penalties possible for crimes—life imprisonment and, sometimes, death. Second-degree murder is often punishable by a life sentence or a term of years.

Death Penalty

More than half of states and the federal government have the death penalty. The death penalty is generally reserved for the worst of the worst.

The Supreme Court has issued several rulings placing limitations on the death penalty. For instance, the Eighth Amendment requires an individualized sentencing process, which means the law can't impose an automatic death sentence on someone. A jury must consider whether a defendant's acts were egregious enough to deserve a sentence of death. Aggravating factors that might support a death sentence include killing vulnerable victims (like a child), killing multiple victims, or killing in a cruel and heinous manner (such as torture). Juveniles and persons with intellectual disabilities cannot be sentenced to death.

Life Without the Possibility of Parole

The next harshest sentence is life without the possibility of parole (LWOP). In most states that don't have the death penalty, LWOP is generally reserved for the worst of the worst. Some states have mandatory LWOP sentences for first-degree murder. It's also a possible sentence for felony murder in certain states. A person sentenced to life without parole will never leave prison.

Life Sentence

Most states allow life sentences for first- and second-degree murder, and some automatically impose it. Life sentences have different meanings in different states. A person with a life sentence is generally eligible for parole after serving a minimum term. This term might be 20, 30, or 40 years (or some other term) depending on the state law. After serving the minimum term, the inmate can apply for parole (early release from prison) but it's not guaranteed.

Sentence of Years

Some states impose a maximum or minimum sentence term for murder (or both), usually for categories falling under second-degree or felony murder. These sentence terms vary but can be decades in length, such as 25 to 50 years. A few states allow sentences up to 99 years, which is considered a virtual life sentence.

Getting a Lawyer

Clearly, murder charges are serious. It's important to seek out legal advice as soon as possible if you're investigated or charged with any type of criminal homicide. Check out these articles for more information: