Learn how redirect and re-cross allow attorneys to clear up confusion and repair any damage done during witness testimony.

Witness testimony plays a crucial role in every criminal trial. Despite what TV shows might suggest, there's no chaos or shouting matches in real courtrooms. Judges keep things orderly, and lawyers and witnesses must follow strict rules about how evidence is presented and how questions get asked. These rules exist to make sure trials are fair and efficient, and so jurors hear reliable information. (Fed. R. Evid. 611.)

Order of Questioning Witnesses

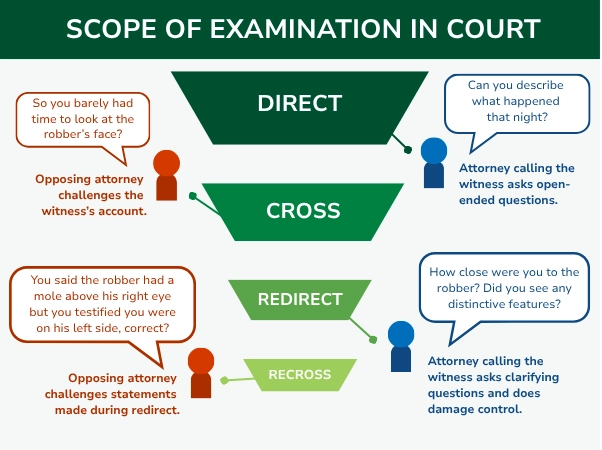

When a witness takes the stand, questioning occurs in the following order:

- direct examination

- cross-examination

- redirect, and

- re-cross.

The attorney calling the witness conducts the direct and redirect examinations. Opposing counsel will cross-examine and, possibly, re-cross the other party's witness. Each side presents its own witnesses, so the lawyers' roles will change depending on who calls the witness.

Below, we focus primarily on the last two types of questioning—redirect and re-cross. But to get there, we need to discuss the boundaries set in direct and cross-examination.

Prequel to Redirect and Re-Cross

The scope of redirect and re-cross examinations (when and if they happen) will depend on the questions and answers provided in direct and cross-examination. Except for clarifying questions or credibility challenges, each stage of questioning is limited to what was asked in the previous stage.

Direct examination. In direct examination, the attorney calling the witness can ask open-ended questions to help guide the witness in telling their story. Common open-ended questions on direct include: "Can you tell us what happened on the night of January 2nd?", "Could you describe the person who took your money?" and "What happened next?" The attorney's goal is to present a clear and convincing narrative for the jury.

Cross-examination. After direct, opposing counsel has a chance to question the witness through cross-examination. Cross-examination allows the lawyer to challenge the witness's story or credibility. The lawyer can use leading questions—questions that suggest the answer within them. For instance, "You said the robber wore a hood and carried a gun, is that correct?" "And most of your attention was drawn to the gun." "So you barely had time to look at the robber's face?" The aim is to test the witness's account, point out inconsistencies, and shift the jury's perspective.

Once each side has questioned the witness, the judge may allow redirect and re-cross.

What Is Redirect Examination?

Redirect examination presents an opportunity for the original attorney to question their witness again after cross-examination. The attorney might decline to redirect when cross-examination wasn't damaging. However, even in this case, the attorney might want the advantage of having the last word on their witness.

Purpose of Redirect

Redirect is generally used to clarify testimony, do damage control, and challenge any negative inferences raised during cross-examination. Or, suppose the cross-examining lawyer inadvertently elicited information damaging to their own case. In that case, a redirect can present an opportunity to exploit that mistake and seek further explanation of the topic.

Attorneys typically only ask a few redirect questions, as they are limited to topics brought up on cross-examination and want to maintain the jury's interest. Redirect is not the time to rehash what was already said on direct examination.

Examples of Redirect Examination

Generally, attorneys must use open-ended questions again during redirect. However, the judge might permit the attorney to use leading questions in an effort to pinpoint a specific matter.

Redirect to clarify or expand. Leading questions permitted during cross-examination can result in yes-or-no answers, preventing the witness from providing an explanation or giving a complete answer. The attorney can use redirect to clarify their witness's answers or to elicit more context. For example, let's say the witness answered "Yes, but…." when asked about focusing on the gun more than the robber's face. On redirect, the attorney could prompt the witness to finish what they wanted to say. "You said you saw the gun pointed at you. Did you also see the robber's face?" "How close were you to the robber?" "Did you see any distinctive features?"

Redirect to repair damage to credibility. During cross-examination, opposing counsel might also try to damage the witness's credibility. The lawyer might point out inconsistencies between what the witness said at the scene and what they said later at the police station. On redirect, the attorney could ask their witness to explain the inconsistencies. "When you spoke to the police at the scene, how long did the interaction last?" "How long was the interview when you went to the station?"

Judges are not going to let redirect veer off course. Their goal is to keep testimony fair and focused.

What Is Re-Cross Examination?

Re-cross presents an opportunity for opposing counsel to address the subject matter discussed in redirect, particularly anything that's new. Judges might not allow re-cross unless new information came up during redirect.

Purpose of Re-Cross

If new information pops up in redirect, judges will usually allow the opposing counsel to point out any weaknesses or test the clarifications made during redirect.

Example of Re-Cross

In the redirect example above, the witness testified to seeing the defendant's face. Opposing counsel on re-cross might attempt to point out weaknesses in this testimony. For instance, opposing counsel might say, "You testified you saw the robber's face and noticed he had a mole above his right eye, correct? You also said the robber was constantly looking at the door, which would have given you a view of the left side of his face, correct? Not the right side?"

Most witness questioning won't get to re-cross, but in the event it does, it should be short and to the point.

Working With Your Lawyer

Your criminal defense lawyer or public defender will guide the strategy when it comes to witness questioning. They must make decisions in the moment. But you can help by preparing with your lawyer ahead of time and answering their questions honestly.