A big difference exists between these two types of warrants. Learn how to tell them apart and what limitations apply to ICE warrants.

During the Trump Administration, ICE raids and arrests have ramped up around the country. Agents are knocking on doors, raiding workplaces, and detaining people they suspect of breaking immigration rules. These aggressive tactics have brought immigration law—and its overlap with criminal law—into the public eye. This article discusses what powers ICE agents generally have to make arrests, enter homes, or hold people, as well as what rights undocumented individuals have when dealing with ICE.

- Understanding ICE's Enforcement Authority

- What Is an ICE Administrative Warrant?

- What Is a Judicial Warrant?

- Warrantless Arrests: When Can ICE Act Without a Warrant?

- Immigration Questions Without a Warrant

- What Rights Do Noncitizens Have When Arrested?

- Finding an Attorney in Immigration Enforcement Cases

- Additional Resources on ICE and Immigration Enforcement

Understanding ICE's Enforcement Authority

ICE—short for Immigration and Customs Enforcement—is part of the Department of Homeland Security and is in charge of enforcing U.S. immigration laws. Under federal law, ICE agents can arrest and detain noncitizens they believe are in the United States illegally or are deportable. The level of that power changes based on whether ICE agents have an administrative warrant, a judicial warrant, or no warrant at all.

ICE Administrative Warrants vs. Judicial Warrants

For civil immigration matters—such as being in the United States without authorization or lawful status—ICE typically uses administrative warrants. Administrative warrants have not been signed off by a judge. For this reason, they don't permit ICE agents to arrest a person in their home or another private place without consent to enter.

To arrest someone in their home, ICE needs an actual judicial warrant, signed by a judge, showing probable cause of a crime. This crime can be an immigration-related crime (for example, forging documents, illegal entry to the United States, or smuggling people) or any crime (like assault, theft, and drug crimes).

ICE Authority Without a Warrant

ICE agents can also make warrantless arrests or detentions in limited circumstances. Agents need probable cause to believe the person is in the country illegally and might flee. Sometimes, the probable cause for the arrest or detention comes from answers provided during a brief encounter in public or questioning at a job worksite or other private space ICE has been allowed to enter. It's best not to answer any questions in these types of situations.

(8 U.S.C. §§ 1226, 1357 (2025).)

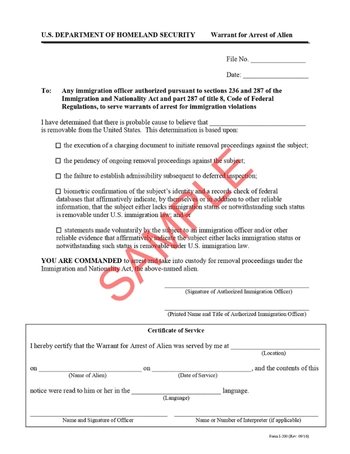

What Is an ICE Administrative Warrant?

An administrative warrant is signed by an ICE officer or another authorized immigration official—not a district court judge. It will typically list:

- the person's name

- the name or seal of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security or another federal agency

- a title such as "Warrant for Arrest of Alien," and

- the signature of an authorized officer or immigration judge (who's different from a judge in federal or state court).

These ICE warrants allow arrests in public spaces, such as hospital waiting rooms, courthouses, schools, and workplace parking lots. They don't let ICE enter homes or private areas (like a hospital room) without permission (consent) or a judicial warrant.

If an agent knocks on your door with only an administrative warrant, you don't have to open it. Even cracking it open can count as giving consent. You can keep the door shut and ask the agent to slide the warrant under the door or hold it to a window for you to read through the glass. If it's an administrative warrant, you can ask them to leave.

Businesses face similar rules. They're not required to let ICE in just because ICE shows an administrative warrant. If they do let them in, though, ICE agents can ask employees about their immigration status, but employees don't need to answer.

What Is a Judicial Warrant?

A judicial warrant changes the rules. A judge signs off on it only after reviewing sworn statements that a person committed a crime—an immigration-related crime (such as illegal entry or document fraud) or any crime (such as assault, theft, and so on). Remember, simply being in the United States without permission is a civil violation, not a crime.

What's in an Arrest or Search Warrant?

A typical judicial arrest warrant includes:

- the court's name (for example, U.S. District Court)

- the accused person's name

- information supporting the charge against the accused person, and

- the judge's signature.

If it's a search warrant, it will state:

- the address to be searched

- the date and time the search can happen, and

- what items officers are looking for.

With a judicial warrant, you must let officers in and comply with the search or arrest. However, you still have the right to remain silent and request a lawyer. (It's best to state clearly you are choosing to remain silent or present the officer with a Red Card.)

Examples of Arrest and Search Warrants

Below are examples of arrest and search warrants.

Warrantless Arrests: When Can ICE Act Without a Warrant?

Sometimes, ICE doesn't need a warrant to make an arrest. Federal law allows warrantless arrests if:

- the agent sees someone entering or trying to enter the United States illegally, or

- the agent has "reason to believe" the person is in the United States illegally and is likely to flee before a warrant can be obtained.

"Reason to believe" means there's enough evidence for a reasonable person to conclude the individual is here illegally—it's not just a hunch or gut feeling. Courts treat it like probable cause.

Being a flight risk can be shown by undisputed evidence of illegal status—such as a confession—or a combination of other clues, like altered papers, limited or no English-speaking skills, nervous behavior, prior arrests or attempts to flee, or weak community ties.

As with any arrest or detention, you can assert your right to remain silent and ask to speak with a lawyer.

(8 U.S.C. § 1357(a)(2) (2025); Au Yi Lau v. U.S. I.N.S., 445 F.2d 217 (D.C. Cir. 1971); Contreras v. U.S., 672 F.2d 307 (2d Cir. 1982).)

Immigration Questions Without a Warrant

The same law for warrantless arrests lets ICE agents stop you briefly or question you about your immigration status. Because these encounters are less intrusive than an arrest, ICE agents don't need probable cause.

Routine Questions From ICE Agents

ICE agents can talk to people they encounter and briefly ask questions. This encounter must stay a short, voluntary conversation—otherwise it becomes a detention. You can refuse to answer and ask if you are free to leave.

Brief Investigative Detention by ICE Agents

If an agent has reasonable suspicion that you're in the United States illegally, they can detain you briefly to question you on your immigration status. If you're not free to leave, you've been detained. You can assert your right to remain silent and ask to speak to a lawyer before answering any questions. (Answering their questions can give the agent a basis to formally arrest you.)

Race and Reasonable Suspicion

What ICE officers need to establish "reasonable suspicion" of someone's unlawful presence remains a controversial topic. In the recent Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo case, the Supreme Court effectively said agents can consider race or ethnicity—though not as the only factor—alongside other clues, like location, type of work, or accent, when assessing whether the person might be in the country illegally. Here, ICE agents were targeting people working at car washes, day laborer pickup sites, and agricultural sites—places that Justice Kavanaugh (in his concurrence) said "often do not require paperwork and are therefore attractive to illegal immigrants." The dissent warned that this risks unfairly targeting "anyone who looks Latino, speaks Spanish, and appears to work a low wage job." (606 U.S. ___ (Sept. 8, 2025).)

(8 U.S.C. § 1357(a)(1) (2025).)

What Rights Do Noncitizens Have When Arrested?

Noncitizens in the interior of the United States have Fourth and Fifth Amendment protections. (Remember, at or near the border, these protections may be reduced.)

Fourth Amendment Protections

The Constitution protects citizens and noncitizens from unreasonable searches and seizures. If an ICE agent doesn't have a judicial warrant, you can refuse entry into your home and refuse to consent to a search (remember, the officer doesn't have to tell you this). You can also refuse to unlock your phone or share passcodes (or ask to speak to an attorney before doing so).

Officers might demand to enter your home or look in your bag, rather than ask for consent. No matter how it's phrased, you can refuse consent. If officers force their way into your home or search you anyway, it's best not to resist. This can be unlawful and dangerous. Fourth Amendment protections also prohibit officers from using excessive force during an arrest.

Fifth Amendment Protections

You have the right to remain silent and to request an attorney during questioning or after an arrest. Some states require you to identify yourself to police, but that doesn't extend to answering immigration-related questions. Never lie or give false documents such as a fake green card, work permit, or Social Security card.

Finding an Attorney in Immigration Enforcement Cases

Whether you're in immigration court or criminal court, you need an attorney.

Criminal charges. When facing criminal charges or being questioned about a crime, you can ask for a government-paid attorney. This is typically a federal or state public defender. Don't answer any questions without speaking to an attorney first.

Civil immigration violations. You have the right to an attorney in most civil immigration cases, such as a deportation or removal hearing. But you must find and pay for the attorney yourself. Ask for a list of pro bono attorneys (who may provide free or low-cost legal services). Don't sign any papers until you speak with an attorney.

Additional Resources on ICE and Immigration Enforcement

Check out Nolo's Immigration page for articles that answer complex questions on the fundamentals of immigration law in easy-to-understand language.

Here are some additional places to find information and help:

- National Immigrant Justice Center: Know Your Rights: If You Encounter ICE

- National Immigration Law Center: Know Your Rights: What to Do If You Are Arrested or Detained by Immigration

- ACLU: Immigrant Rights

The U.S. government also has FAQs on Immigration Enforcement.

- Understanding ICE’s Enforcement Authority

- What Is an ICE Administrative Warrant?

- What Is a Judicial Warrant?

- Warrantless Arrests: When Can ICE Act Without a Warrant?

- Immigration Questions Without a Warrant

- What Rights Do Noncitizens Have When Arrested?

- Finding an Attorney in Immigration Enforcement Cases

- Additional Resources on ICE and Immigration Enforcement