What does it mean to be a "pass-through" tax entity in the eyes of the IRS?

For many small businesses, paying income tax means struggling to master double-entry bookkeeping and employee withholding rules while ferreting out every possible business deduction. For partnerships, paying taxes also involves understanding difficult terms like "distributive share," "special allocation," and "substantial economic effect." Here, we demystify some of these complexities and explain the basics of how partnerships are taxed.

How Partnership Income Is Taxed

Generally, the IRS doesn't consider partnerships to be separate from their owners for tax purposes; instead, they're considered "pass-through tax entities." This classification means that all of the profits and losses of the partnership "pass through" the business to the partners, who pay taxes on their share of the profits (or deduct their share of the losses) on their individual income tax returns.

Each partner's share of profits and losses is usually set out in a written partnership agreement (discussed later). As a pass-through business entity owner, partners in a partnership might be able to deduct 20% of their business income with the 20% pass-through deduction established under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

Filing Tax Returns

Even though the partnership itself doesn't pay income taxes, it must file Form 1065 with the IRS. This form is an informational return the IRS reviews to determine whether the partners are reporting their income correctly.

The partnership must also provide a Schedule K-1 to the IRS and to each partner, which breaks down each partner's share of the business's profits and losses. In turn, each partner reports this profit and loss information on his or her individual tax return (Form 1040), with Schedule E attached.

Estimating and Paying Taxes

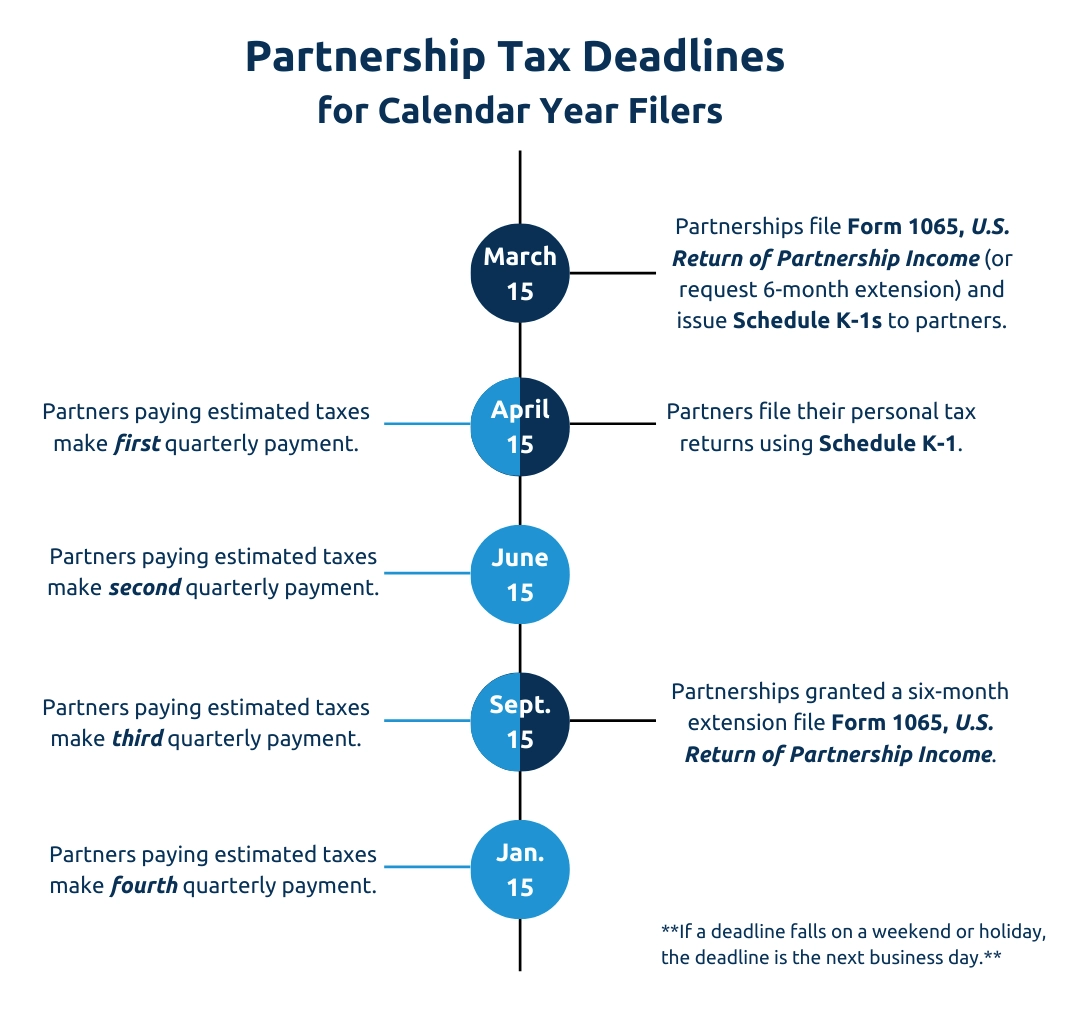

Because there's no employer to compute and withhold income taxes, each partner must set aside enough money to pay taxes on their share of annual profits. Partners must estimate the amount of tax they'll owe for the year and make payments to the IRS (and usually to the appropriate state tax agency) each quarter—in April, June, October, and January.

Why You Need a Partnership Agreement

If you want control over how profits and losses are distributed to you and your partners, creating a partnership agreement is critical. You can outline each partner's share of the business's profits and losses in your agreement. Because you have a better understanding of how much of a role each partner plays in the partnership, you're in a better position to allocate profits. If you don't have a partnership agreement or your agreement is silent on this term, your state's laws will decide what each partner gets.

Some states say that each partner is entitled to an equal share of the profits. Other states say that a partner's entitlement depends on their capital contributions or ownership percentage. Whatever your state's allocation rules, it's best that you and your partners decide on a distribution scheme that works for everyone.

For example, suppose Deniz and Phylicia run a dog grooming partnership. Phylicia is in charge of the business relationships and financial responsibilities. Phylicia also works five of the six days the business is open. Deniz has invested time in other business ventures and only works one day at the shop and occasionally orders new inventory. Phylicia and Deniz agree that because of Phylicia's heavier workload, she should be entitled to 70% of the profits, and Deniz should be entitled to 30% of the profits. They memorialize these terms in a partnership agreement.

Now, suppose that Deniz and Phylicia never created a partnership agreement. Instead, their partnership terms relied on their state's laws. Their state's laws dictate that partners are entitled to an equal share of the profits. So even though Phylicia does most of the work in the business, she'd only be entitled to 50% of the profits per state law.

Profits Are Taxed Whether Partners Receive Them or Not

The IRS requires each partner to pay income taxes on their "distributive share." This share is the portion of profits to which the partner is entitled under a partnership agreement—or under state law, if the partners didn't make an agreement.

IRS Taxes Partners Based on Their Distributive Share

The IRS treats each partner as though they've received their distributive share each year. As a result, you must pay taxes on your share of the partnership's profits—total sales minus expenses—regardless of how much money you actually withdraw from the business.

The practical significance of the IRS rule about distributive shares is that even if partners need to leave profits in the partnership—for instance, to cover future expenses or expand the business—each partner will owe income tax on their rightful share of that money. (If your business will regularly need to retain profits, you should consider incorporating—corporations offer some relief from this particular tax bite.)

Establishing the Partners' Distributive Shares

Unless business partners make a written partnership agreement that says otherwise, state law usually allocates profits and losses to the partners according to their ownership interests in the business. This allocation determines each partner's distributive share.

For instance, suppose Andre owns 60% of a partnership and Jenya owns the other 40%, Andre will be entitled to 60% of the partnership's profits and losses, and Jenya will be entitled to 40%. (In addition, state law assumes that each partner's interest in the business is in proportion to the value of their initial contribution to the partnership.)

If you'd like to split up profits and losses in a way that's not proportionate to the partners' percentage interests in the business, it's called a "special allocation," and you must carefully follow IRS rules.

Self-Employment Taxes

If you're actively involved in running a partnership, in addition to income taxes, the IRS requires you to pay "self-employment" taxes on all partnership profits allocated to you. Self-employment taxes consist of contributions to:

- Social Security, and

- Medicare.

Self-employment taxes are similar to the payroll taxes employees must pay. However, there are some differences between the contributions regular employees make and the contributions partners must make.

- First, because no employer withholds these taxes from partners' paychecks, partners must pay them with their regular income taxes.

- Second, partners must pay twice as much as regular employees because employees' contributions are matched by their employers. However, partners can deduct half of their self-employment tax contribution from their taxable income, which lowers their tax bill a bit.

Partners report their self-employment taxes on Schedule SE, which they submit annually with their personal income tax returns.

Business Expenses and Deductions

You might be wondering how you'll survive financially after paying income taxes, Social Security taxes, and Medicare taxes on your share of business income, even if you don't withdraw it from your business. Luckily, you don't have to pay taxes on most of the money your business spends to make a buck.

You and your partners can deduct your legitimate business expenses from your business income, which will greatly lower the profits you have to report to the IRS. Deductible expenses include:

- start-up costs

- operating expenses

- travel costs

- product and advertising outlays, and

- a portion of the money you spend on business-related meals and entertainment.

In addition, many states are now implementing a pass-through entity (PTE) tax to offer relief to PTE owners, like partners in a partnership. Ordinarily, as discussed above, partners would pay taxes on their share of the partnership's income. But if your partnership elects to pay the PTE tax, then the partnership itself would pay taxes on behalf of the partners. You and the other partners would then claim a tax credit on your personal return.

As a result, your partnership can claim a federal business expense deduction for the state income tax payments it made through the PTE tax. Claiming the deduction would then lower the income reported by your partnership, thus lowering your share of that income and reducing your federal income tax burden.

Incorporating Your Business May Cut Your Tax Bill

Unlike a partnership, a corporation pays its own taxes on all corporate profits left in the business. Owners of corporations pay income taxes only on money they receive as compensation for services (salaries and bonuses) or as dividends.

While many small businesses would rather not file a corporate tax return, incorporating can offer business owners a tax advantage over a partnership's "pass through" taxation. This is especially true for businesses that expect to retain profits in the business from year to year.

If you need to keep profits (called "retained earnings") in your business, you might benefit from lower corporate tax rates. For example, if your retail outfit needs to stock up on expensive inventory, you might decide to leave $30,000 in your business at the end of a year. If you operate as a partnership, these retained profits will likely be taxed at your marginal individual tax rate, which is probably more than 25%. But if you incorporate, that $30,000 will be taxed at a lower 21% corporate rate.

To get a better idea of whether you should incorporate to reduce taxes, see our article on how corporations are taxed.

Get Expert Help for Business Taxes

If you're confused by partnership taxes, you're not alone. A good way to learn the basics is to read Tax Savvy for Small Business, by Glen Secor (Nolo). Then, plan to get the help you need from a tax adviser who specializes in partnership taxation to make sure you comply with the complex tax rules that apply to your business and stay on the good side of the IRS.