Learn about the most common types of nursing home abuse, who's likely to be responsible, the kinds of claims you'll bring, proving liability and damages, and more.

According to data from the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation, as of July 2024, more than 1.22 million residents lived in one of the 14,827 certified nursing homes in the United States. Most nursing home residents are women, and almost half suffer from dementia or other cognitive deficits.

Nursing homes are chronically understaffed. Patient care workers are undertrained, underpaid, overworked, and generally ill-prepared to manage and care for residents who need daily, specialized, physical and psychological care. It's a recipe for resident mistreatment.

If you're considering a lawsuit for nursing home abuse or neglect, you've come to the right place. We start by describing the most common types of abuse and the warning signs to look out for. From there, we'll explain who can be liable for abuse-related injuries, how to bring and prove a lawsuit, the damages you can collect, and more.

What Is Nursing Home Abuse?

Nursing home abuse—physical, psychological, sexual, or financial mistreatment or neglect that puts a resident in danger of harm or that causes actual harm—is a widespread and underreported problem. It's hard to say just how widespread the problem is because comprehensive, reliable data aren't widely available.

The Most Common Forms of Abuse and Neglect

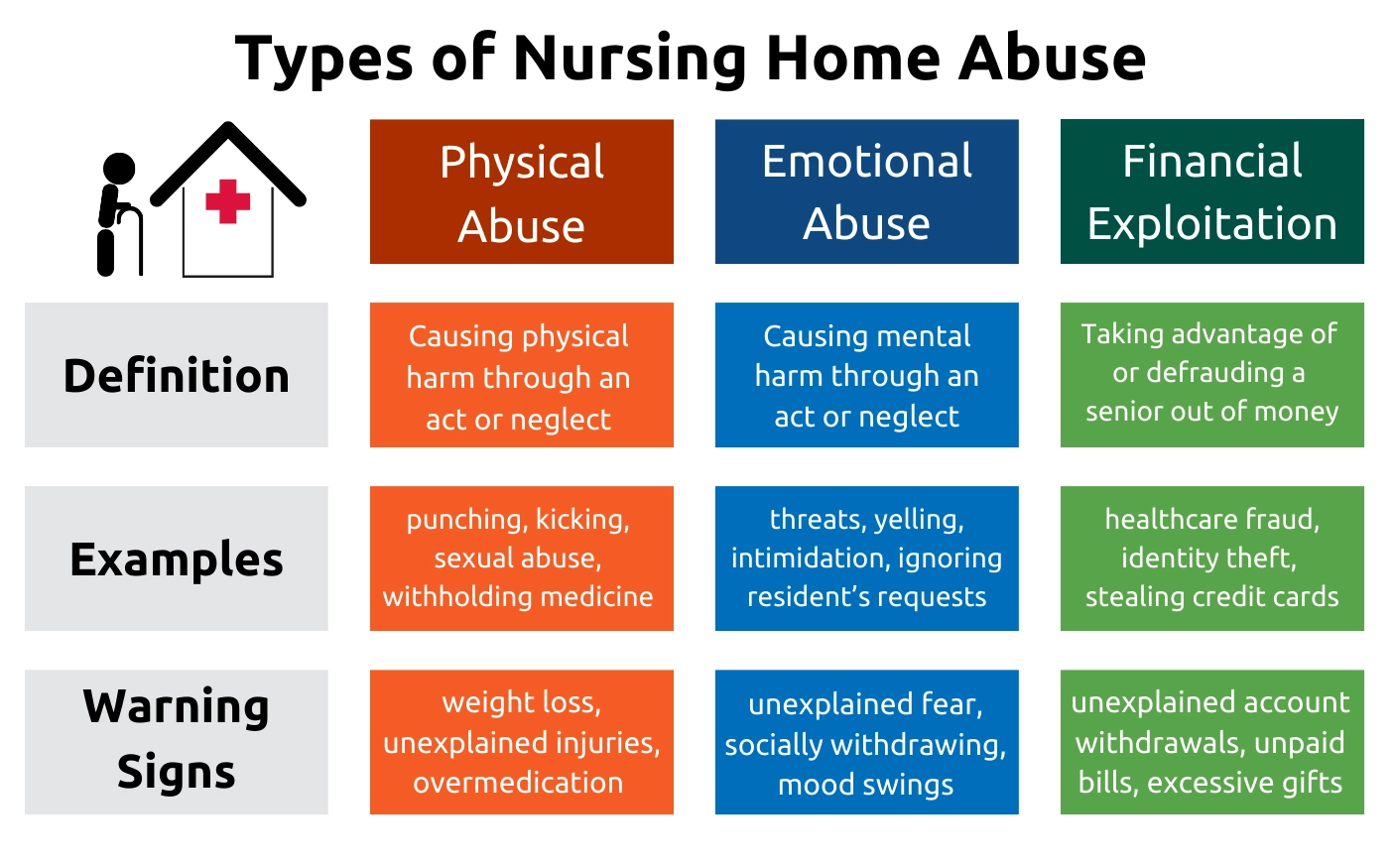

The most common forms of nursing home abuse and neglect include:

- physical abuse and neglect, including sexual abuse

- psychological abuse, including verbal abuse, and

- financial exploitation.

Perpetrators of abuse can include nursing home staff, other residents, family members, and third parties like contractors.

Physical Abuse

Physical abuse typically involves the intentional infliction of physical harm, such as slapping, punching, kicking, and excessive use of physical or chemical restraints. It includes sexual assault of residents, usually women with cognitive deficits. Withholding prescribed medications—or the administration of prohibited medications—also falls into this category.

Possible warning signs of physical abuse include:

- sudden weight loss

- dehydration or malnutrition

- bedsores

- overmedication, including over-sedation

- unexplained injuries, such as broken bones, sprains, bruises, scrapes, and cuts

- trauma—such as bleeding, bruising, or swelling—to the genitals, anus, the genital area

- torn or bloodied undergarments

- a sexually transmitted disease, and

- unexpected signs of restraints on the wrists or legs.

Physical Neglect

Physical neglect includes any deliberate or negligent failure to provide for a resident's physical or medical needs. Red flags include:

- lack of basic hygiene or clothing

- dirty or soiled undergarments, clothing, or bedsheets

- unexpected weight loss

- untreated bed sores or pressure ulcers, and

- failure to provide glasses, a walker, dentures, hearing aids, or medications.

Psychological Abuse

Psychological or emotional abuse includes deliberate acts or omissions meant to cause anxiety, anguish, fear or other mental harm. Common forms include threats, yelling, harassment, intimidation, physical isolation, and ostracization. Emotional abuse can also occur through passive behavior, such as intentionally ignoring a resident's requests or other needs.

In addition to many of the same signs present with physical abuse, be on the lookout for:

- excessive fear or apprehension around certain people

- rocking, sucking, or mumbling—called "false dementia"

- social withdrawal

- refusal to speak, particularly regarding conditions at the facility

- a caregiver who's verbally aggressive, uncaring, or demeaning, and

- sudden and unexplained fear, sadness, depression, anxiety, or other behavioral or personality changes.

Financial Exploitation

Elderly people are particularly susceptible to fraud and exploitation. Nursing home residents—whether due to cognitive decline or physical limitations—often must rely on others for such basic tasks as reading mail, paying bills, or managing bank accounts.

Three types of financial abuse are widespread:

- bank account and credit card theft

- internet scams, and

- healthcare fraud.

Caregivers often have access to residents' financial accounts and information, sometimes leading to identity theft, diversion of benefits (like Social Security), or worse. Older people also are prime targets for scams. Solicitations from non-existent charities or threats of legal or enforcement actions by scammers posing as government authorities are common.

Healthcare fraud happens when a provider charges for equipment or services that are unnecessary, are never actually provided, or are included in the cost of other covered services.

Warning signs of financial exploitation include:

- frequent, unexplained bank account withdrawals

- new loans or mortgages

- unexpected changes to wills, deeds, or powers of attorney, or giving control of financial affairs to a caregiver

- giving excessive and unexpected gifts, particularly to non-family members

- suspicious additions of beneficiaries to life insurance policies

- disappearance of personal property or money

- caregivers' inability to explain the need for particular equipment or treatment

- billing insurers or medical providers for health care services that were never provided

- unexpected charges to credit cards or withdrawals of account funds, and

- unpaid bills.

What's the Scope of the Problem?

In general, it's fair to say that nursing homes have high rates of abuse. But reliable data are hard to come by, in part because abuse and neglect are underreported. Residents often fear retaliation if they report mistreatment.

Small, focused studies sometimes offer telling insights. In one survey of 452 adults with relatives at a Michigan nursing home, more than 24% reported that their relative had experienced at least one incident involving physical abuse. In another study, over two-thirds of all caregivers—when allowed to speak anonymously—self-reported that they'd physically abused at least one resident.

Ninety-five percent of nursing homes—more than 14,000 facilities—have been cited for one or more deficiencies, meaning a problem that can "result in a negative impact on the health and safety of residents." And 28% were flagged for at least one "serious deficiency," meaning a problem that has caused a resident to suffer actual harm, or a problem that has caused "serious injury, harm, impairment, or death to a resident receiving care in the nursing home."

Who's Liable for Nursing Home Abuse and Neglect?

When residents are harmed by abusive or neglectful behavior, the victim (or their representative) can sue:

- caregivers, contract workers, third parties, and others who directly cause the harm

- the nursing facility, along with its supervisory and managerial staff, and

- employers of responsible caregivers, contract workers, and third parties.

The nursing facility and other employers can be responsible in two ways. First, they might be "vicariously liable" for their employees' negligent misconduct, meaning they can be made to pay for their employees' wrongdoing. In addition, they can be liable for their own wrongful acts, like:

- negligent hiring of staff or contractors

- negligent failure to supervise or monitor staff, residents, and third parties

- understaffing

- inadequate training

- violation of statutory or regulatory obligations, and

- medical and nursing errors.

What third parties and contractors might be on the hook? Nursing homes often outsource tasks like food service, cleaning, and security to third-party providers. Vendors like delivery and equipment repair companies also have access to nursing facilities.

Suppose a nursing home hires a security company. Another resident—or a guest visiting the nursing home—assaults a resident, causing injuries. The security firm might be legally responsible if its negligence contributed to cause the attack.

Contact Authorities for Help

If you suspect abuse or neglect and it's an emergency, dial 911. Police and first responders can provide help and protection.

Once you've done that—or if you suspect abuse but it's not an emergency—contact your state's Adult Protective Services (APS) office. Here's a list of state APS and similar agencies you can call for assistance.

While APS's authority varies from state to state, it's likely the first line of investigation for claims of nursing home abuse or neglect. When APS isn't able to help, they'll refer your report to the responsible state licensing or regulatory agency.

If APS is legally authorized to take a case on, it will investigate, create and implement an assistance plan, and revise the plan as necessary. APS works with the resident, family members, care providers, and other social and legal services agencies to fix the problem and make sure the resident receives appropriate care.

You can also contact your state's long-term care ombudsman. Among other things, ombudsmen are advocates for nursing home residents. They work to resolve issues associated with resident care. They also investigate individual complaints of nursing home abuse, neglect, and exploitation.

You'll find more information at the National Long-Term Care Ombudsman Resource Center.

Filing a Lawsuit

If you or a family member has been injured and you want to recover personal injury damages (or if your relative died and you want to collect wrongful death damages), you can file a civil lawsuit. Most often, your lawyer will sue in the state's main trial court.

You start a lawsuit by filing a document—most states call it a "complaint"—with the court where the defendant lives or (if it's a company) has its main place of business. The parties you sue ("defendants") will respond with an "answer." Don't be surprised if they deny all your allegations—that's standard practice.

From there, the case enters a period known as "discovery." The parties exchange documents and information, depose witnesses, and prepare the case for trial. As the party who filed the lawsuit (the "plaintiff"), you'll be deposed, too. If you can't settle the case, it goes to trial. Expect this process to take between 12 and 18 months, longer if there's a post-trial appeal.

(Learn more about the personal injury lawsuit timeline.)

Proving the Case at Trial

If the case goes to trial, the plaintiff's lawyer must prove each element of the plaintiff's legal claims. In a nursing home abuse case, there likely will be claims for:

- intentional wrongdoing against the individual abusers, and

- careless misconduct, called negligence, against the nursing home.

Intentional Wrongdoing

When a nursing home resident is physically abused, the law calls it an "intentional tort." In the context of nursing home abuse, the most common intentional torts are assault and battery. To prove these claims, the plaintiff must show that an abuser intentionally caused the victim to fear imminent harmful or offensive contact (an assault), or intentionally caused harmful or offensive contact (a battery).

When nursing home staff prevent a resident from leaving a certain area—say, their room or a wing of the facility—it might be an intentional tort called false imprisonment. Here are a few ways abusers might confine a resident:

- leaving them without their wheelchair, a walker, or crutches

- physical or chemical restraints

- locking them in their room or another part of the facility

- threatening them with harm, or

- threatening to withhold food, water, or medication.

Negligence

The plaintiff likely will bring negligence claims against the facility and maybe others, as described above. To prove negligence, the plaintiff must show that:

- the nursing home owed the resident a duty of care (meaning a duty to act reasonably carefully, given the circumstances)

- the nursing home breached that duty of care (it did something it shouldn't have done, or failed to do something it should have done), and

- the breach of duty caused the resident to suffer harm.

Damages in a Nursing Home Abuse Case

A successful plaintiff most often will collect "compensatory damages." As the name suggests, these damages are meant to compensate for injuries caused by a defendant's wrongdoing. Compensatory damages come in two varieties:

- economic damages, and

- noneconomic damages.

Economic Damages

These damages reimburse the plaintiff for amounts they're out of pocket because of the abuse. In a nursing home case, the biggest category of economic damages will be medical and hospital bills related to treatment for the plaintiff's injuries. If your relative dies as a result of abuse, economic damages also will include amounts you pay for their funeral and burial costs.

Noneconomic Damages

These damages are meant to compensate for injuries and losses that the plaintiff doesn't pay directly out of pocket. Included are injuries like pain and suffering, emotional distress, and loss of enjoyment of life. These damages can be substantial in a nursing home abuse case, but many states have put arbitrary limits, called "caps," on noneconomic damages in injury cases.

Punitive Damages

Punitive damages don't compensate the plaintiff for their losses. Instead, they're meant to punish a defendant, and to deter similar behavior by others. Punitive damages usually aren't awarded in injury cases, but the plaintiff might win them if they can prove a particularly egregious pattern of abusive or neglectful mistreatment.

Proving Damages

For the court to award damages, there must be evidence that the plaintiff suffered harm. As a rule, evidence of economic damages will be easier to come by than evidence of noneconomic damages.

For instance, nursing home injuries often require medical care. The plaintiff's medical records create a paper trail detailing the history of abuse, a list of physical and emotional injuries, and the plaintiff's resulting treatments. Medical bills prove the amounts the plaintiff (or their medical insurer) paid for care.

Proving noneconomic damages—pain and suffering, for example—can be more challenging. Medical records should (but might not) document complaints of pain, nursing observations of discomfort, and administration of pain medicine. The plaintiff (or others speaking on the plaintiff's behalf) will need to testify about the pain, its severity and duration, and how it impacted the plaintiff's daily activities.

The plaintiff, their family members, and others should document the abuse and the plaintiff's injuries as completely as possible. Proof that can be useful includes:

- diaries kept by the plaintiff or family members

- photographs of the plaintiff's bruises or other injuries

- notes summarizing conversations with the plaintiff and with nursing home staff

- photographs of medications given or prescribed to the plaintiff, and

- notes on personal observations of physical or emotional conditions.

Nursing Home Abuse Lawsuit FAQ

Here are some other questions you might have about filing a nursing home abuse lawsuit.

Who Can Sue for Nursing Home Abuse?

When the abused resident is alive and is legally competent to sue, they'll be the plaintiff. If the resident is alive but incompetent, they'll need a guardian or conservator—as discussed above—to sue on their behalf. When the abused resident has died and family members want to pursue a wrongful death lawsuit, the case will be filed by a surviving relative or the executor of the resident's estate.

How Difficult Is It to Sue a Nursing Home?

It's tempting to think that a nursing home case should be easy to prove. An elderly, defenseless resident, usually suffering from physical problems and cognitive deficits, gets beat up or exploited by staff. Cases don't get much easier than that, right?

Not so fast. For starters, don't expect any cooperation from the facility or its staff. In fact, don't be surprised if you encounter active efforts to cover up the abuse, particularly if there's a longstanding pattern of wrongdoing. If word gets out that a facility has a history of abusing and exploiting residents? That's bad for business.

Depending on the claims raised in the lawsuit, the parties you're suing, and your state law, a nursing home case might be a type of medical malpractice suit. As a rule, malpractice claims are legally complex, time consuming, and expensive. You'll want to consult with legal counsel before deciding to sue.

What's the Statute of Limitations on a Nursing Home Abuse Case?

The statute of limitations is a deadline on the time you have to file a lawsuit in court. Every state makes its own statutes of limitations. You'll need the advice of a lawyer to know what the filing deadline in your case will be.

If it's an ordinary personal injury case, most states allow between two and five years to sue. But if it's a medical malpractice case, expect a shorter deadline—likely just one to three years.

Do I Need a Lawyer for a Nursing Home Lawsuit?

Yes, you need an experienced nursing home abuse lawyer in your corner. This is someone who knows how far too many nursing homes operate, how to investigate and find evidence of abuse and neglect, and how to put together a compelling case for trial.

When you decide to move forward with your case, here's how to find the attorney who's right for you.

Talk to a Lawyer

Need a lawyer? Start here.

How it Works

- Briefly tell us about your case

- Provide your contact information

- Choose attorneys to contact you

- Briefly tell us about your case

- Provide your contact information

- Choose attorneys to contact you